Out on the Wire: The Storytelling Secrets of the New Masters of Radio is Jessica Abel’s investigation—in comics form—of how exceptional radio shows such as This American Life and Radiolab collect, curate, and shape nonfiction stories. Abel first met Ira Glass in 1999, when she collaborated with him on Radio: An Illustrated Guide, a 32-page comic book that takes readers behind the scenes of TAL.

Since the publication of Out on the Wire and its accompanying podcast series on creativity, Abel has been traveling widely in the U.S. and in Europe, giving workshops about nonfiction narrative techniques, visual storytelling, and many other subjects related to the creative process. This January, she visited the Carlow MFA program to help nonfiction, fiction, and poetry students develop effective language to talk about their manuscripts and their own creative processes. Afterwards, she and Carlow MFA director Kevin Haworth visited a Pittsburgh tapas restaurant to discuss contemporary comics, teaching strategies, and many other subjects. (Abel has an encyclopedic knowledge of tapas and an extensive Spanish vocabulary.)

That led to the following more planned, but still free-flowing, Skype conversation for Proximity about nonfiction comics.

KH: Thanks for agreeing to do this. I know you’ve been on a deadline. How’s the current project?

JA: Good. Working on the new book, Growing Gills. What do you think of that title, by the way?

KH: I like it. Tell me more about it.

JA: It builds on the work that I’ve been doing coming out of Out on the Wire. This is a book about creative focus.

KH: Oh, I like the title even better now.

JA: Glad to hear it.

KH: I’m going to use this opportunity to talk about nonfiction in the comics world, following up on Out on the Wire. In the creative writing world, we think a lot about what it means to write fiction versus writing nonfiction. For comics artists, that discussion doesn’t seem to come up as much. What’s your sense?

JA: You mean, do comics artists divide themselves so concretely?

KH: Yes. In creative writing programs, it’s structural—you’re taking nonfiction workshops, or fiction workshops, and so there’s a lot of discussion around what that means.

JA: So far, in comics, there are no programs that divide it up that way. There’s a lot of flow in the comics world between fiction writers and nonfiction authors that are working in memoir or personal stories. Comics journalists are a bit different. They might do some memoir but mostly they are journalists. They really do identify as nonfiction writers and talk about the role played by reporting and research and sources in their work.

KH: So there’s the comics journalists over here, and the people who are doing character-driven narrative over there.

JA: Well, there’s a spectrum, of course, and memoir is the middle ground. Fiction writers might do memoir, and comics journalists might do memoir, but fiction writers rarely move into the comics journalism realm or vice-versa. People like Josh Neufeld and Joe Sacco are firmly on the journalism end. They both have done memoir comics, but even their memoir comics have a very reportorial approach. But there are lots of ways that nonfiction comics are doing character-based stories. It’s not just reportage. There are people right now doing memoirs having to do with medical issues. There’s lots of history comics too. There’s a new comic about Andy Warhol, and one about Harry Houdini, and one about Ernest Shackleton. There are comics about science, math, philosophical subjects. There’s an incredibly wide range of nonfiction comics. And that’s because comics aren’t a genre; it’s a medium. It’s a narrative medium, so it spans the entire range of possibility. There’s comics poetry, for example.

KH: You make a really important point—the range of nonfiction comics is much broader than people may realize. More than I realized before this conversation, and I read a lot of comics. Take something like [John Lewis’s] March, for example. It’s a nonfiction comic. Or Lauren Redniss’s Radioactive, about Marie Curie. Some of these have become really important comics, but they don’t fit neatly into memoir or comics journalism.

from Radioactive by Lauren Redniss

JA: Even Out on the Wire is not comics journalism. It has journalistic elements—I interviewed people—but I’m following a thesis. It’s really an essay. Staying with books about the radio world, Josh Neufeld’s book with Brooke Gladstone [The Influencing Machine] is an essay.

KH: That’s such a great book. I love that book.

JA: It’s a great book.

KH: I wouldn’t have used that word, essay, but it’s a really useful word for this kind of comic. It’s a long essay. A long essay in comics form?

JA: What would you call it? Because I struggle with that too.

KH: A longform narrative? Longform is a term of art these days.

JA: That’s too imprecise. A profile could be longform.

KH: You’re right. I’ll need to do some more research. Maybe our readers will tell us.

JA: I have a student who’s creating a comic book about Depo-Provera, the birth control injection. She’s an academic, a tenured professor of anthropology, and now she’s trying to move from academic work to work that’s, let’s say, more readable, and she’s trying to do that in comics form. To me, that’s an essay, but essay suggests something short. And this is going to be a long book.

KH: I’ll put my people on it. My nonfiction people.

JA: It would be helpful to have a word to describe it.

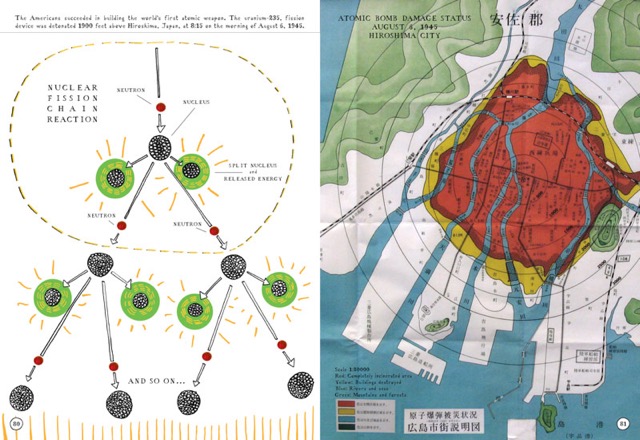

KH: I think it’s important, generally, for readers to have more of a sense of the range and impact of nonfiction comics. March comes to mind as a good example, because it’s gotten so much great attention lately. But there are some incredibly influential comics that don’t fall neatly into Alison Bechdel memoir or Joe Sacco journalism. There have always been “explainer comics”—comic books that convey the basic ideas of, say, Marxism or Freud, and a lot of people grew up learning from those. Today’s biography and science comics are much more sophisticated and aesthetically interesting versions of those.

JA: There are nonfiction comics that do an incredibly good job of explaining ideas. One of the pivotal comics for me was Larry Gonick’s The Cartoon History of the Universe. I read that when I first graduated from college. [Abel first started making comics while a student at University of Chicago.] I had read a lot of history, but seeing it in comics form was important. He has a very particular point of view about how history works—focusing on movements of people and connections between historical epochs and different peoples. He gave me a sense of “what is history” that I had never gotten from my history classes.

KH: That leads into the next question—what were your models for doing Out on the Wire?

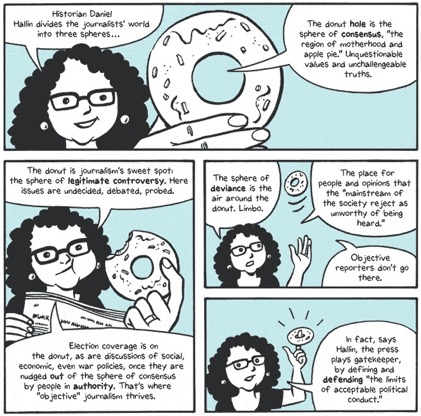

JA: I looked very closely at The Influencing Machine and talked to Josh about how he put his book together. Partly because of the radio connection, and also because there are ideas in it. How do you convey ideas in comics form? How do you make a concept into a concrete image? He used a technique that I had also used back in Radio: An Illustrated Guide. It’s the Abstracted Avatar. In Josh’s book, a visually simplified version of Brooke Gladstone is always talking, leading the reader through the book. So I resurrected that. It adds a meta-layer—of me, or Ira Glass, or other characters, who can talk about what’s happening in the “actualities,” to use radio-speak.

from The Influencing Machine by Brooke Gladstone and Josh Neufeld

KH: That’s the great breakthrough of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics.

JA: That’s where I got it from! When I was working on Radio: An Illustrated Guide, in 1998 and 1999, I borrowed the technique from Understanding Comics.

KH: This helps explain why books like Understanding Comics, which I’ve taught dozens of times, or Out on the Wire, which I used in a Carlow University undergraduate class last year, are such effective teaching tools. You have an avatar who serves as a stand-in for the reader.

JA: Exactly. And one way I built on this technique—though I didn’t realize it until I was deep into working on the material—is to use interns at the radio shows as avatars, as stand-ins for students. I did it in Radio: An Illustrated Guide, though I don’t think I realized what I was doing at first. When writing about Transom Workshop for Out on the Wire, Julia DeWitt—who’s now a big-time, fancy producer, but at the time was totally green, learning everything—I followed her around as she learned and depicted that in the book. It mirrors what the reader is doing, learning everything as you go along.

from Out on the Wire by Jessica Abel

KH: There’s something technical that’s happening in each of these books that allows the reader to place themselves right there in the pages.

JA: And it’s something you can’t replicate, not exactly, in prose. You can have a narrator, and the narrator might say, “Pay attention to this,” but there’s no visual distinction. There’s nothing that forces the cognitive recognition that there’s two layers happening here—the people doing the action, and the people learning about the action. I literally have my characters walk into a panel, when there’s something important happening in the background, and point at it, and say, “Look at what’s going on right here.” That actually mimics teaching. When you teach a text, you pause and say to the students, “Look at this.”

KH: And then, as the teacher—as in a comic book—you might let the action roll forward a little bit, and then say to the students, “Pause, and look at me, and let’s discuss this.” The comics panel becomes a stand-in for the classroom.

JA: It’s possible to do it in prose—you can bold something, or highlight it, or repeat it—but it tends to be clunky. When I tried to write a novel, I felt as if I were writing with one hand tied behind my back. There are lots of things that prose is great at, of course. But if I were trying to depict an action scene, I would have to explain where everything was. In comics, you just make a picture. It’s all there.

Cartoonist and writer JESSICA ABEL is the author of Growing Gills, Out on the Wire, La Perdida, and two textbooks about making comics, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures and Mastering Comics. Abel’s new science fiction comics series, Trish Trash: Rollergirl of Mars, debuted in November 2016. She is Chair of the Illustration Program at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and lives with her family in Philadelphia.

Cartoonist and writer JESSICA ABEL is the author of Growing Gills, Out on the Wire, La Perdida, and two textbooks about making comics, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures and Mastering Comics. Abel’s new science fiction comics series, Trish Trash: Rollergirl of Mars, debuted in November 2016. She is Chair of the Illustration Program at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and lives with her family in Philadelphia.

KEVIN HAWORTH is a 2016 National Endowment for the Arts fellow and Director of the low-residency MFA program at Carlow University. His books include the novel The Discontinuity of Small Things, winner of the Samuel Goldberg Fiction Prize; the essay collection Famous Drownings in Literary History; and the limited edition essay chapbook Far Out All My Life. His collection of essays about writing, Lit from Within: Contemporary Masters on the Art and Craft of Writing, co-edited with Dinty W. Moore, was recognized as an American Library Association Outstanding Title, as one of Writer magazine’s Top 10 Writing Books, and listed as one of Poets & Writers’ Best Books for Writers. He has held residencies at Vermont Studio Center, Headlands Center for the Arts, and Ledig International Writers House. Before coming to Carlow, he taught at Ohio University and at Tel Aviv University. His newest project, Rutu Modan: War, Love and Secrets, is a book-length study of Israel’s most prominent comics artist.

KEVIN HAWORTH is a 2016 National Endowment for the Arts fellow and Director of the low-residency MFA program at Carlow University. His books include the novel The Discontinuity of Small Things, winner of the Samuel Goldberg Fiction Prize; the essay collection Famous Drownings in Literary History; and the limited edition essay chapbook Far Out All My Life. His collection of essays about writing, Lit from Within: Contemporary Masters on the Art and Craft of Writing, co-edited with Dinty W. Moore, was recognized as an American Library Association Outstanding Title, as one of Writer magazine’s Top 10 Writing Books, and listed as one of Poets & Writers’ Best Books for Writers. He has held residencies at Vermont Studio Center, Headlands Center for the Arts, and Ledig International Writers House. Before coming to Carlow, he taught at Ohio University and at Tel Aviv University. His newest project, Rutu Modan: War, Love and Secrets, is a book-length study of Israel’s most prominent comics artist.

Leave a Reply