Spring in North Carolina is almost Edenic. Rising temperatures usher in porch-sitting, my favorite seasonal pleasure, before the summer humidity, before mosquitos. My neighbors and I emerge from hibernation to renew friendships, spend long days gardening and long nights reading or sipping under string lights we keep up all year. Paradise. Except: spring ushers in the return of the cockroach. This nasty creature plagues my porch. They have wings here. They fly from porch rail to porch rail onto me and, when I’m forced inside, they often follow, slipping through unsealed window frames.

When I began to study Japanese haibun and haiku this spring, I was startled to see kudzu, cockroaches, and azaleas—all markers to me of contemporary southern culture—in poetry translated across centuries. This recognition of myself and my environment in poetry from across time and geography is at the heart of Clinton Crockett Peters’ philosophy of environmental writing. He believes that as climate change affects every denizen of the earth, environmental writing has the potential to be a hotbed of inclusivity.

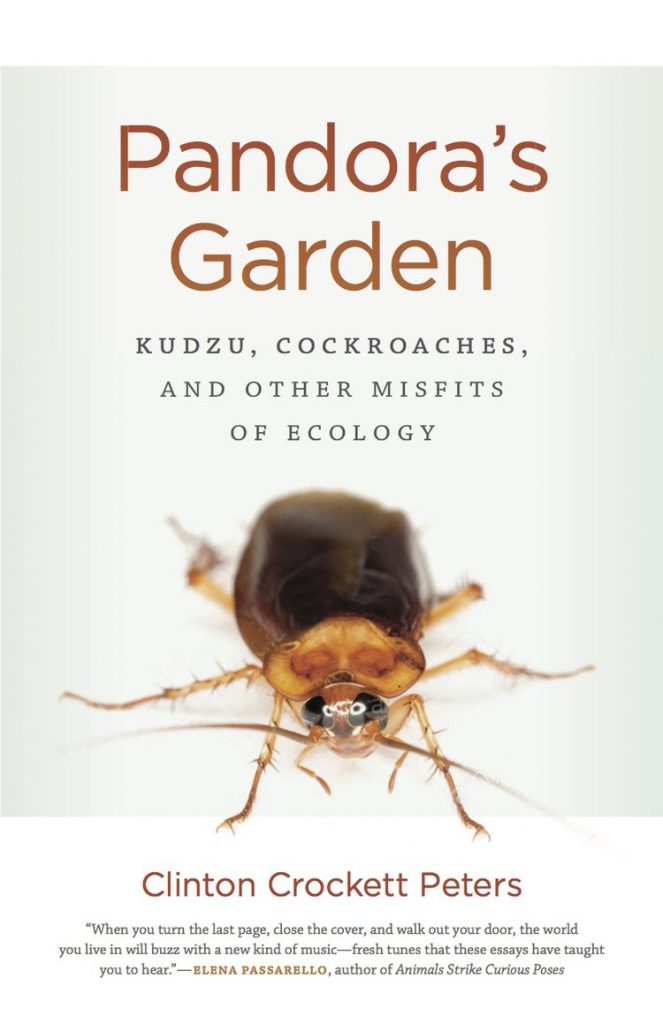

The cockroaches had just launched their summer invasion when I began to read Pandora’s Garden, Clinton Crockett Peters’ debut collection of essays that explores invasive species and questions how our reactions to these misfits and our instinct to exterminate or to evolve alongside them reflects how we treat human misfits in society as well. Outside my home I practice loving kindness. I study yoga and meditate on the principle of ahimsa ‘do no harm.’ Still, I stomp, crush, and drown cockroaches.

Clint is an environmentalist who, until recently, taught at University of North Texas. This fall, he will join the faculty at Berry College in Georgia as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing. His essays tackle fascinating and important subject matter, but I found myself laughing outloud, swept away by humor in his voice and images. In my interview, I ask him about his writing and research process, learn about his eco-writing philosophy, and swap reading recommendations and resources for the environmental writing workshop with him.

Morgan Davis: Pandora’s Garden is chock-full of these fascinating facts about not only invasive species, but film, history, news, people, civic planning, the law. How do you conduct your research?

Clint Peters: I’m old school, I like doing work in libraries. I find libraries conducive to creative thinking. It’s something of osmosis being around words and ideas. This quiet place, this reverential tone. I teach at University of Texas right now and we have a pretty wonderful library, except that everyone goes there. It’s called the Willis Library. For Pandora’s Garden I got to research cockroaches and Asian carp and Texas snow monkeys, all these fun, weird, quirky, some of them gross things, and a lot of it didn’t make it out of the cutting room, a lot of it sloughed away. There’s a rabbits and convicts essay that’s near the beginning, and I just went down so many rabbit holes with that.

Some of my research is hands on—I have this essay on the world’s largest rattlesnake roundup. They bring thousands of rattlesnakes into this giant colosseum and just pour them on the floor. It’s crazy, the hum of all those rattles is absolutely surreal. It’s like staring into deep space or something. That was close, I could go there and get hands on experience I wanted. I toyed around with going to Australia for my rabbits essay, but I don’t have that kind of money and I figured I just didn’t need too. A lot of it is historical. When I can, I like to go places and see things. Different essays required different types of research. Science journals, science books at the library, interviews. For the carp essay, a lot was through news media.

MD: What was the most surprising fact you unearthed while researching Pandora’s Garden?

CP: Oh, gosh, there were so many facts. In the Godzilla essay I found out that both the director and composer suffered radiation poisoning. Godzilla is often dismissed as a kitchy thing, for a good reason. After the first it turned into that, but the first I think is a cinematic masterpiece. By the way, for readers, don’t watch Godzilla King of the Monsters with Raymond Burr, watch the original. The Americanized version bastardizes the movie. The whole movie is about expressing the dire straits of the nuclear situation at the time, and also expressing nuclear trauma. There’s a moment on the subway train that was cut from the Americanized version where a man and a woman are like, “Oh, Godzilla’s attacking? Are we going to go back to the shelters? I still feel sick from the last time.” And it’s just this random moment where nuclear radiation was this everyday thing, which it was, and bombings were this everyday reality for people in Japan that Americans just didn’t sit well with.

So many facts about the Asian carp just blew my brain away, like how much it can eat. Like 70% of its body weight in food every day. No wonder things are dying in the Mississippi and other places. And that states were suing states to close the canal to stop the fish, I think that’s bonkers. Oh! One million camels live in the Australian outback. Camels are not from Australia, they’re just roaming around!

MD: How do you weave in your research—is ‘weave’ even the right word?

CP: I kind of see my essays as collages. Usually how I work with a research-driven piece, like “Texas Snow Monkeys,” is I have these different individual sections, sometimes paragraphs or a couple of paragraphs. I’ll polish them, and those’ll be my little collage stones. I’ll put them in the essay and switch them around. I’ll take pieces out, I’ll make new pieces, and put them back in. I don’t know if that’s the best way to work but it’s the only way I can work because thinking of a whole essay is overwhelming unless I think in terms of chunks. In the chunk I can think in terms of sentences. Then you branch it out to the book, and I can break down the whole project so it doesn’t get overwhelming, which it often does.

I actually had a fact-check on my book which is an interesting process, and by interesting I mean nerve-wracking. It was…oh boy. I obviously got some facts wrong. I do a pretty good job at keeping sources clear, but I’ll admit I still need to improve in that area. If I’m doing some research and really liking what I’m finding, I’ll start riffing. I like that because it’s part of my process: that’s how I inject my own creative voice into the material, riffing off research, using it as a platform or springboard and then I’ll just get into it and the separation between my words and the source blur. One of my good friends Toni Jensen—

MD: Toni Jensen!

CP: Do you know Toni?

MD: “In the Time of Rocks” is one of my favorite Ecotone stories.

CP: I love that story! So she’s doing research and doing the same riffing thing, but she’s smart: when she starts riffing, she picks up a different color pen. When she told me that, I was like, “Oh! Why haven’t I been doing that for years?” Or if you riff on the laptop, change the font or something. These are both good ideas from Toni.

MD: You’re writing about these different invasive species and I love that you coin them misfits. Do your friends call you now when they have a surprising misfit wildlife encounter? Are you now the cockroach friend?

CP: Yeah! You know what, that has happened. I put this out there on the record: I don’t like cockroaches. There’s a cockroach on my book cover and that was my idea. I’m not a fan. They still weird me out. But that’s part of what that essay’s about: why am I weirded out? Can I analyze my fears and paranoias? In my cockroach essay there’s a horrific story: My friend George went to sleep and he woke up and felt something in his ear.

MD: Oh no.

CP: It was what you think it was. He said if he had a gun he would have shot himself. And he means that literally. So creepy and terrifying. He went to the doctor, who tonged it out. What’s really crazy is that’s not super uncommon. My friends love telling me similar stories. Another thing I’ve become is the Godzilla guy. Why is Godzilla in a collection of invasive species? I think he is the ultimate invasive species, his projection of human consciousness.

The thing about misfits is—do you feel this way? I feel like a lot of writers do—I felt like a misfit as a kid. I didn’t feel like I got along with other children. A lot of that was internal: internal anxieties and insecurities. But for whatever reason I’ve always identified with people who don’t seem to fit in. Thinking about cockroaches or Asian carp or snow monkeys, maybe we hate these things but why? Can we give these things their due? Cockroaches are scavengers. They’ve lived with people since people have been around. They’re weird and they do give kids asthma but they’re not as disgusting or nearly as deadly as mosquitos. Mosquitos are horrendous but people don’t tend to scream when they see them, although they probably should. With Zika and Dengue! That’s a flying plague. It’s interesting that cockroaches are what gets the fear but what actually kills us is more of an annoyance.

Feeling like a misfit as a kid led me to wonder ecologically: is there a way to think of these creatures differently? What role do they have to play? As long as people are around they’re going to be around. Kudzu is another example. Can we evolve with kudzu, into a new kind of way of living with this misfit that people actually brought here? People actively planted kudzu, people really wanted kudzu. Kudzu only did what kudzu does, which is try to survive.

MD: It’s interesting to think of the human role, especially with the snow monkeys. A lot of these creatures are victims of human decisions. Which makes me think of another point in the book: we see a reflection of ourselves and how we treat others in how we treat these natural misfits.

CP: That was a huge contribution from my friend Tom Huang, who’s one of the editors at Dallas Morning News. We were doing a workshop at the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference—a book proposal workshop. He turned to me and said, “Clint. Looking at these creatures, we see how people treat other people.” That was a nice light bulb that went off, a thread I was trying to draw, seeing how we value or disvalue, or use rhetoric, terms like invasive, to determine who’s included in the community. A misfit is only a misfit because the community collectively decides it. It’s not preordained by the universe. This led to interesting conversations about inclusion. In the Snow Monkey essay I talk about how Texas treats its immigrants, which is not well. No surprise.

MD: I just read your Essay Daily about pushing against traditional nature writing and calling out Edward Abbey for his horrible anti-immigrant notions.

CP: Thanks for reading that! That’s kind of like my manifesto. I put a lot into that—what we can do as environmental writers and environmental beings, and what we’re not doing.

MD: It feels like it should be required reading. What really hit me hard was when you divulge how Edward Abbey just eliminated his wife and child who lived out with him from his work. Talk about erasing of women in literature! It could have been a more interesting story.

CP: That would have been a cool story, too, I agree. The thing about eco-writing is its inclusivity, right? Everyone is affected by their environment. I don’t know if you can say that about many things. We’re all going to be affected by climate change. Some more than others. That’s why I think eco-writing and eco-criticism are such vibrant fields right now, because of all of these connections you can draw between the snow monkey to climate refugees to food desert to ecojustice to water shortages to the Flint Water Crisis. The Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment Conference is, I think, well over a thousand people, and it started in one little hotel room at the Western Literature Association Conference. Now it’s probably bigger than its parent. ASLE was in Detroit last year, it was a great outing. Ross Gay was there.

MD: He’s amazing.

CP: There’s just so much to talk about. Eco-writing connects us, right? In ways that reveal how vulnerable we are, but also how strong we can be because we are connected. We all eat food, we all need air and water. People have this view that eco-writing has to be this boring in-your-face preachy thing, and it doesn’t have to be. It can still have something it wants to say but it doesn’t have to say it. To pick on Edward Abbey, he took a tone of superiority and know-it-all-ism that I don’t think is very good, and is also emblematic and systematic of white male supremacy. There’s a lot being done right now in eco-criticism to undo that, to undo the heteronormativity and white supremacy that has plagued environmental writing—as it has everything. If we want to help inclusivity it’s time to move on from the Edward Abbey-types.

MD: Have you read Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem? Tin House published it. it’s one of those books that gets me so excited about language that I put it down and start to write. He’s a person to replace the heteronormative old-white-guy-with-beard image of nature writing. What other writers can we add to the list of expanding the boundaries of eco-writing?

CP: I’ll definitely check that out! I’d suggest my friend Taylor Brorby. He has a book about fracking in North Dakota, and he’s a wonderful human being. My friend Angela Pelster, her book Limber is so, so good. Elana Passarello’s Animals Strike Curious Poses is one of my favorite books of last year. She does so much research and it’s so fun. She writes about famous animals like Leo the Lion or Jumbo the Elephant or Mozart’s canary. So insightful, it goes places that are unexpected but also super rewarding. Jericho Parms’ Lost Wax—one of those books that, like you said, got me wanting to write. Where does it intersect with mine? She does a lot of research and mixes it with the personal—art history, travel writing, Roman mythology, Roman history.

MD: You’re teaching at UT currently, what environmental writing resources do you recommend, what essays excite you for teaching eco-writing?

CP: Luis Alberto Urrea, he’s one of my favorites. Devil’s Highway has to be in my top five. It’s groundbreaking, it floors me. I assign excerpts from that every semester. I think the world of him. Priscilla Ybarra’s has a really good book called Writing the Good Life. I think it’s a wonderful example of an accessible academic text that has a personal stake. If you want to teach something that has textual analysis that’s environmental but still very insightful and just well-written, Priscilla’s really clear.

Assign local writers who write about the local environment so you can bring them into the classroom. Strangely enough, George Getschow, the bug-in-the-ear guy, wrote this earth-shattering story about the Lake Lewisville Dam, upstream from Dallas. During the floods we had in 2015, the dam was nearing capacity and the Army Corps of Engineers was trying to keep this silent. But there was actually a chance the dam could burst, because it’s just eight miles of earth, and earth is earth and water can move earth if it wants to. I live in the blast zone. It would be this wall of water rushing through a lot of the Dallas suburbs, including my apartment. His story won some awards, it got some recognition, and actually it got the Army Corps of Engineers to be more transparent. My students get kind of awed when the author comes into the classroom. It gives the work a life of its own, that this is a real life breathing person. I brought George in and Priscilla, too, they were great. And Skype. Actually writers, living and breathing makes writing seem like more than a chore, makes it seem like they invest in their work in a way I find really helpful.

MD: In “Snow Monkeys,” you’re also writing about these Texan identities and ethics of animal treatment and gun laws. You avoid preaching on the subject, but I detect a tone of empathy. Do you think there’s a responsibility to not state an opinion, like traditional journalism? Can we reach more people with creative nonfiction if we let people draw their own conclusions?

CP: I don’t like sermonizing. In earlier drafts I do notice I start having this axe to grind, especially since I’m an environmental hippie kind of guy and I care about the world and it sucks to see a lot of it go up in flames. But I don’t think guilt trips work, they backfire. Guilt trips and sermonizing come from a place of superiority and I just don’t see people as superior to each other. We’re all pretty ignorant in our own ways. We’re all still animals, in a good way. Like the snow monkeys. Empathy and sympathy come from our primate ancestors. We’ve inherited that as a tool of survival and group cohesion. These are good things. Compassion is a wonderful evolutionary strategy for sustainability. Recognizing the animality still in humanity is one of my big projects.

I want to explore things and gesture and hint and let people draw their conclusions. I have a lot of opinions. I try to tone those down because I want to have fun. People who read want to have fun. In my view of writing there’s enough seriousness and enough overseriousness. I hope the fun and humor is apparent. Enough people feel like environmental writing is just eating your vegetables. I’m trying to do something different with the genre that’s more palatable to people’s taste because for too long it’s just felt like one big sermon. Sermonizing comes from a place of assumed superiority, and I don’t have that. I don’t think any environmental writer has that. Our hands are all bloody.

MD: That leads me to ask about when “Clint” comes into an essay. When does the “I” exist in creative nonfiction and when doesn’t it? You spent time in Japan and time in Texas, and this essay follows a creature from Japan to Texas, so it seemed to me like a draft could exist where you are in the story more, talking about assimilation.

CP: I had a draft, almost twenty pages longer, where I talked about living in Japan and wanting to see the Texas snow monkeys. There’s this famous bath, this tourist attraction, where you can take a bath with a snow monkey. Which is kind of weird, you know? They poop in that water! But people pay good money to go swim in monkey poop, it’s fascinating. I think it’s for the photo-op, the photos do look neat. I was hanging out with my then-fiancée now-wife and she didn’t really want to go do this. She was like, “These monkeys live all over Japan, they’re around where you live, you don’t need to go to freakin’ Nagano to go hang out with them.” It was this reverse codification. Instead of them being these misfit invasive creatures they were this precious tourist attraction—except they weren’t a rarity. That’s when I dropped the idea altogether, the parts about me living in Japan feeling out of my element, living in a village of 900 people. I was the white dude in the village. I did that for three years and didn’t speak the language until I got over there, and it was an adjustment and cultural immersion.

I workshopped this in my MFA and people just didn’t seem interested in that. Frankly neither was I. For me the interest was the snow monkeys. My journey didn’t have as much tension. It wasn’t life or death, first of all, it was a way more comforted kind of immersion. I could always go home. It was my choice to be there and I could always choose to leave and the snow monkeys? It wasn’t their decision, they didn’t want to leave their mountain. The tension around me paled in comparison. I jettisoned a good ten, twelve pages of personal material. Part of the issue was I was looking for a voice or thread or a character to carry through the story. Lawrence Wright called it the donkey of the story: who carries it. In the collection I have an essay about mass extinctions and it’s much more personal, I do come in. I have the story of my dad who slowly died from cancer over a period of eleven years. I feel like that connects well with mass extinctions in a way my story didn’t connect well with snow monkeys. Does that make sense?

MD: It makes so much sense. It reinforces principles of craft. One: it has to be life or death, at least in the character’s own mind, and two: the tension is where you have to write.

CP: Yeah! And when I decided to jettison my stuff, I realized I needed more snow monkey material and that’s when I got the nerve to Skype with the scientist in Japan. He gave me a lot of helpful information. So like that whole Jaws thing—the shark wouldn’t work so Spielberg and his crew had to do other things to make the movie scary—it made it a better movie. That sounds really conceited, me comparing myself to Jaws.

MD: After this interview I won’t be able to sleep with my new fear of cockroaches! I live by the beach and love swimming and diving—I will never see Jaws now; I don’t want to be scared of sharks, too.

CP: Sounds like a good plan.

CLINTON CROCKETT PETERS is the author of Pandora’s Garden: Kudzu, Cockroaches, and Other Misfits of Ecology from the University of Georgia Press. He has been awarded literary prizes from Shenandoah, North American Review, Crab Orchard Review, Columbia Journal, and the Society for Professional Journalists. He holds an MFA from the University of Iowa, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow, and a PhD in English/creative writing from the University of North Texas. This fall, he will join the faculty of Berry College as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing. His work also appears in Orion, Southern Review, Texas Monthly, Fourth Genre, The Rumpus, Hotel Amerika, Electric Literature, and elsewhere.

CLINTON CROCKETT PETERS is the author of Pandora’s Garden: Kudzu, Cockroaches, and Other Misfits of Ecology from the University of Georgia Press. He has been awarded literary prizes from Shenandoah, North American Review, Crab Orchard Review, Columbia Journal, and the Society for Professional Journalists. He holds an MFA from the University of Iowa, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow, and a PhD in English/creative writing from the University of North Texas. This fall, he will join the faculty of Berry College as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing. His work also appears in Orion, Southern Review, Texas Monthly, Fourth Genre, The Rumpus, Hotel Amerika, Electric Literature, and elsewhere.

FREDERICA MORGAN DAVIS earned her MFA in Fiction from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. There she served on Chautauqua Journal‘s editorial staff as proofreader and podcast host, staffed Ecotone Magazine, interned for Lookout Books, and co-directed the Young Writers Workshop. She is an alumna of Lit Camp, Tin House, and One Story summer writing workshops and will attend Bread Loaf Environmental Writers Workshop in June 2018. Her stories have placed in the Top 25 for Glimmer Train’s Short Story Award for New Writers and been a finalist for the Doris Betts Fiction Prize.

FREDERICA MORGAN DAVIS earned her MFA in Fiction from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. There she served on Chautauqua Journal‘s editorial staff as proofreader and podcast host, staffed Ecotone Magazine, interned for Lookout Books, and co-directed the Young Writers Workshop. She is an alumna of Lit Camp, Tin House, and One Story summer writing workshops and will attend Bread Loaf Environmental Writers Workshop in June 2018. Her stories have placed in the Top 25 for Glimmer Train’s Short Story Award for New Writers and been a finalist for the Doris Betts Fiction Prize.

5

Leave a Reply