by Joelle Renstrom

In 1987, my fourth grade teacher asked us to imagine life 25 years in the future and to describe, in complete sentences and legible cursive, our future selves and the state of the world. I didn’t understand the power of setting an imagined future to paper. I’d recently written about a pig on a cruise liner and about a macaroni noodle that had adventures with a spoon. “Life in 2012” didn’t seem so different. It was just a story.

*

A couple Christmases ago, while cleaning baby clothes, trophies, and old toys out of my mom’s basement, I found a box that contained a stack of schoolwork, including a folder on which I’d written “Life in 2012” in red crayon. Inside the folder, brainstorming maps, the edges curled with age. Atomic structures with bubbles connected by lines and ideas scratched out in pencil about my personal achievements, lifestyle, and what the world might be like. Furious scribbles obscured possibilities that existed only fleetingly in my imagination until I thought of something better.

In my imagined 2012, I train dolphins in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I eat Peanut Butter Crunch cereal for breakfast every morning (I loved it so much I couldn’t imagine my future without it) before driving to work in the black Porsche I purchased with all my dolphin cash. In my imagined future, I work miracles with a whistle and a bucket of fish. I have a talking alarm clock and a robot named Fester.

In the actual future, in the now, I write and teach classes about robots. This I’ve always considered to be one of my life’s most unexpected twists. The only memory I have about robots is from a trip to Florida about a year before I wrote the assignment. My older brother told me that for five dollars, I could buy a robotic companion from the Epcot Center gift shop that would follow me around like a pet. I earned and then clung to that money for months and was devastated to learn that five bucks couldn’t even get me a stuffed animal.

*

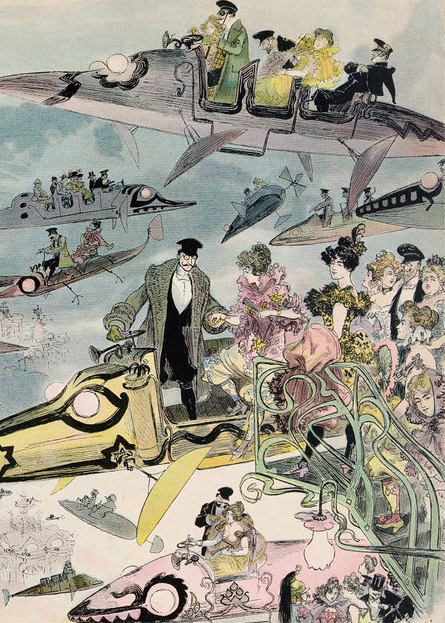

Two years after I completed “Life in 2012,” I modified some details in pencil. I upgraded my Porsche to a flying car with an auto-start and an auto-warming button (I’d recently seen Back to the Future), and at the bottom of one of the pages I added: “I live a simple, easy life unlike most others.” What hard, complicated life did I envision at ten years old? What was I trying to steer myself away from?

Despite my flying car and robot, when I updated my assignment, I also wrote, “I believe in doing work myself, not using expensive machines.” The fact that I teach, read, and write about technological dystopias (they’re what got me into robots) and still refuse to get a smartphone retroactively imbue this comment with meaning that reverberates throughout my body, as though I’ve just discovered a secret about myself. What was happening in my ten-year-old mind that made it important to insert this addendum into an assignment I’d completed two years earlier?

“Life in 2012” feels like a clue to a mystery I hadn’t yet identified or named. It’s a piece of a puzzle—one I never knew existed, which means there are likely countless more. I imagine them in trails, like breadcrumbs, and some of them lead back to the past, to times that feel so settled one hasn’t thought of them in years.

In my futuristic narrative I describe Fester the robot and the dolphins I train, but I don’t mention a spouse, kids, or anyone else. Obsessions punctuated my childhood: macaroni and cheese, hockey, marine mammals, books, writing. I didn’t daydream about marriage or having kids. This never felt strange, or like an omission—I loved what I loved, and had few thoughts for other things. And yet I can’t help wondering what would be different now if “Life in 2012” featured me in the role of wife or mother?

*

According to the multiverse theory, an infinite number of universes exist, created by the choices we make. In another universe, I might be a scuba diving instructor—a fantasy of mine since I took my first breath underwater. In this world, I considered and then chose not to pursue a legal career, but I might be on my way to court in another. Alternate universes don’t have to be upside-down worlds. They can be places where only a few details are different. If parallel worlds exist, they might affect one another. Cal Tech cosmologist Ranga-Ram Chary believes that when universes knock together, each leaves a mark on the other. If that’s true, who knows what fingerprints other universes might have left on the one we currently inhabit?

In science fiction, parallel universes explain that unsettled, not-quite-right feeling. “It doesn’t have to be like this,” a character might say, as though she’s detected a whiff of another, better world. Perhaps there’s a parallel world in which my life is exactly as I described it when I was eight. Perhaps writing the future creates alternate universes, whose inflation is fueled by imagination and hopes and fears. Perhaps that explains why writing is so hard, and how much it can hurt to crash against other realities.

The concept of the multiverse frees us from the pressure to capture history—too many histories exist, affecting too many presents and futures. Possibilities and layers render causal relationships ephemeral—they exist in our minds, fleetingly, as our understanding of the present shifts daily, hourly. So too does the concept of time. Light from stars already dead just now reaches us. Those stars exist in the past, but also in the present, and in the future, somewhere. They defy time. I like to think parallel universes work this way too. Our lives, like Billy Pilgrim’s, could become “unstuck in time,” thwarting linearity by unfolding in countless spaces at once, in countless ways.

*

In considering “Life in 2012” and its effect on the present, I consider Walter Benjamin’s descriptions of the various ways we understand history. “[N]o state of affairs is, as a cause, already a historical one. It becomes this, posthumously, through eventualities which may be separated from it by millennia. The historian who starts from this, ceases to permit the consequences of eventualities to run through the fingers like the beads of a rosary,” Benjamin writes, noting that a fish-eyed, sequential view of the past cannot truly grasp cause and effect. Yet this is how most of us make sense of things—in hindsight, we ferret out causal connections in an attempt to understand the present. But the enormity of the past remains hidden from view. Benjamin argues that “to articulate what is past does not mean to recognize ‘how it really was.’” We cannot separate our recollections of history from our place in the present—we can never know “how it really was,” just as we can never know how it could have been. The past constantly evolves, shifting as time and realities change, and its impact on the present can never be comprehensively assessed. Depictions of the future by an eight-year-old also fall into this category.

*

“Life in 2012” also required us to describe the future world. I had some insight into social and political issues thanks to my parents—my dad, a professor of political science, and my mom, a social worker, and I don’t recall many topics my parents wouldn’t discuss. And yet, I don’t remember talking or even thinking about some of the issues I describe: “drugs have been legalized, but are still a threat,” I wrote. I don’t remember which drugs I knew existed when I was eight or why legalizing them seemed like the best option (DARE didn’t start until the following year). I note that “AIDS and Alzheimer’s disease are both curable”—not surprising, perhaps, given the ravages of HIV in the 1980s, but I don’t remember learning about Alzheimer’s disease, as no one in our family had it yet. Back in 1987, I still had faith in doctors and hospitals.

In my alternate 2012, “pollution and chemicals have caused more deterioration of the Poles, though Styrofoam is no longer used” and “overcrowding in major cities and sometimes jails is a still a big problem.” I boycotted McDonald’s because of its Styrofoam packaging, but I don’t remember learning about the soaring population and overcrowded cities—it would be another 15 years before I lived in one of them.

Skirting around the edges of my future is a fear I couldn’t fully realize or articulate: as good as we are at dreaming up solutions, we’re even better at creating new problems. Even my prediction that Eddie Murphy, Jr. would be president—a nod to my brother, who loved Murphy, and now a reference that trips with almost sadistic irony—reflects a dichotomy between optimism and pessimism, between outlandish fantasy and reality. It makes me wonder about not just the human brain, but the child’s brain, about its firestorms of activity that go unnoticed or unrecorded, and how much power they have.

*

Our teacher invited parents to write versions of “Life in 2012” and my mom enthusiastically complied, envisioning the world she’d live in at age 70. In this imagined future, my dad is still alive and the two of them moved to Virginia after a mini ice age made Michigan uninhabitable. She also predicted AIDS would be cured. Maybe we both took it for granted that scientists would have figured out how to beat cancer by 2012.

In my mom’s 2012, she has a hydroponic greenhouse in which she grows rare tropical plants and she has a robot that does housework. She “photo-phones” her grandkids. The “One World Act” makes traveling a breeze—no passports, visas, or customs lines anywhere, allowing her and my dad to traipse around the world after their retirement. She predicted universal health care (the “Golden Age Policy,” specifically meets the needs of older folks). Concerns of the past 20-30 years, such as nuclear war, pollution, and the greenhouse effect are “relics of the past.” As prescient, ironic, or just plain coincidental as some of these predictions seems, they read like fortune cookies: chunks of information that form their own discrete futuristic truths, rather than a complete picture, just as Benjamin says.

Surprisingly, my mom’s vision of the future is more sanguine than mine. Since when does an adult possess more optimism than a kid? Did she write a futuristic version of a fairytale because she couldn’t bear to write anything else for her eight-year-old’s assignment? Did she think writing down the future—hers, mine, and the world’s—could change it for the better?

*

On a recent visit home, I had my mom read both of our “Life in 2012” papers so I could ask if she had really believed her G-rated version. She said she didn’t pull punches, that back then she believed her vision of the future. My mom is no Pollyanna—she has a tendency to exaggerate miseries and the world rarely seems to live up to her expectations. Her rosy prognostications provide a lesson in context. “Life in 2012” is a time machine that allows us to access who we were and how we saw the world during the fall of 1987—a span of time Mom described as the “golden years” of our family, when I was 8, my brother 16, my dad 44, and my mom 45.

“It’s like we were shielded,” she said when I asked her for more details. Mom counseled kids and facilitated international adoptions, taking care of far more people than her kids. My dad, rock solid and healthy, was fulfilled by work and hobbies. My brother had a driver’s license and a job washing dishes, and I was happily absorbed by school and books. We were a textbook nuclear family, with a dog, two cats, and a yard. We spent summers swimming, fishing, and playing on vacation with my grandparents. I don’t think any of us would have called life perfect, but it’s hard to look back and think of a reason to complain.

It seems clear now that my mom was never happier than she was in 1987. About five years after that, when I was 13, I wondered for the first time if she was unhappy. I had started sensing something, a disquiet. Maybe some part of her knew the golden years were ending. Sometimes I’d catch her with a faraway look, like she was peering into the distance for a glimpse of something she feared she’d never see again.

*

I’m only four years younger now than my mom was when she wrote about the future. Am I at my happiest now, too? I’ve identified a few golden times in my life, but only in retrospect and with paralyzing nostalgia. Can we recognize and truly appreciate the sweet spots while we’re in them? Did my mom know when she wrote “Life in 2012” that she was in her golden years? Part of me hopes so, but part of me hopes not.

*

I imagine what I would write if, were I to have an eight-year-old, she asked me to envision the world in 25 years. What would I say about the climate, class divides, conflict, scientific advancements, or robots? “Life in 2043” might be too terrifying to tuck into a child’s folder. Perhaps I would have to express it in holograms. Or maybe the future would feel unexpectedly bright to as it did to me or to my mom in 1987. I briefly consider writing it, a quick time capsule, but I decide not to. I only want to write it if it envisions a world I’d want to live in—I don’t want to write into existence another dystopian future.

I imagine what would happen if my fourth grade teacher never gave me an assignment to write about the future. Perhaps there’s a parallel universe in which that’s the case. Who am I there? What forces have shaped my life, my future? What lies in the boxes in the basement, waiting to be unearthed, waiting to reveal what might have been, or what elsewhere is?

JOELLE RENSTROM’S collection of essays, Closing the Book: Travels in Life, Loss, and Literature, was published in 2015. She’s the robot columnist for the Daily Beast and a frequent contributor to Slate, and she has been published in the Guardian, Washington Post, and Aeon, among others. She teaches writing and research at Boston University.

1

Leave a Reply